Blogging Chrome

Technical Blog and online Resume

Published by Paolo Riccardi on 29 Sep 2021 in Category [Distributed_Systems]

Introduction

Let’s start from the beginning, the original title was “Dynamo: Amazon Highly Available Key-value Store”, it was published in 2007 and you can download it here. The book itself is a great reference and an interesting reading if you want to know more about distributed systems in theory and practice and it has inspired me up to a point that I had to start a pet project to get my fingers dirty with its contents. For those interested, the pet project is fundamentally a key value distributed datastore, but this will hopefully be covered by another post. A big part of both my BS and MS programmes in Computer Science at University were about distributed systems and as such I was already both familiar with and interested in concurrency related problems. Nonetheless I found the paper very insightful, everything was laid out in a straight line, with a very practical approach that has the merit to underline business outcomes for system design choices.

One of the first things that I’ve noticed, while reading the paper for the first time, is that it’s dense. What’s addressed in a couple of semicolons can easily take pages and pages on an average undergraduate course handbook about concurrency and distributed systems. The paper was so influential that its principles inspired noSQL databases like Apache Cassandra, Riak and, as the name may imply, DynamoDB.

The authors are basically the engineers behind the Amazon Dynamo database, a noSQL data store that was built in house to power many of the company’s business critical services like the ecommerce shopping cart. Given the nature of the service provided, Dynamo was designed to be always on, which translates to a high emphasis on availability.

The reliability and scalability of a system is often dependent on the way its application state is persisted. Relational databases were and still are the one stop shop for pretty much everything, but usually the usage pattern for state persistence is just to store and retrieve data by primary key, without complex queries that rely on articulated relations between entities. In other words in such a scenario, using a RDBMS will mean paying for lots of extra benefits that you won’t use. That’s why for Dynamo a simple key-value approach was chosen.

Here’s the assumptions that were made and the requirements that led the design of Dynamo as described in the paper:

- Query Model - read/write on data items uniquely identified by a key, no relational schema required and no operation can involve more than one data item

- ACID properties - Dynamo will choose Availability over Consistency any day of the week

- Efficiency - The system will work on commodity hardware and will satisfy SLAs such as very low latency

- Non-hostile environment - Dynamo will be used just by internal services

Availability vs Consistency

Spoiler: (in the paper) availability wins.

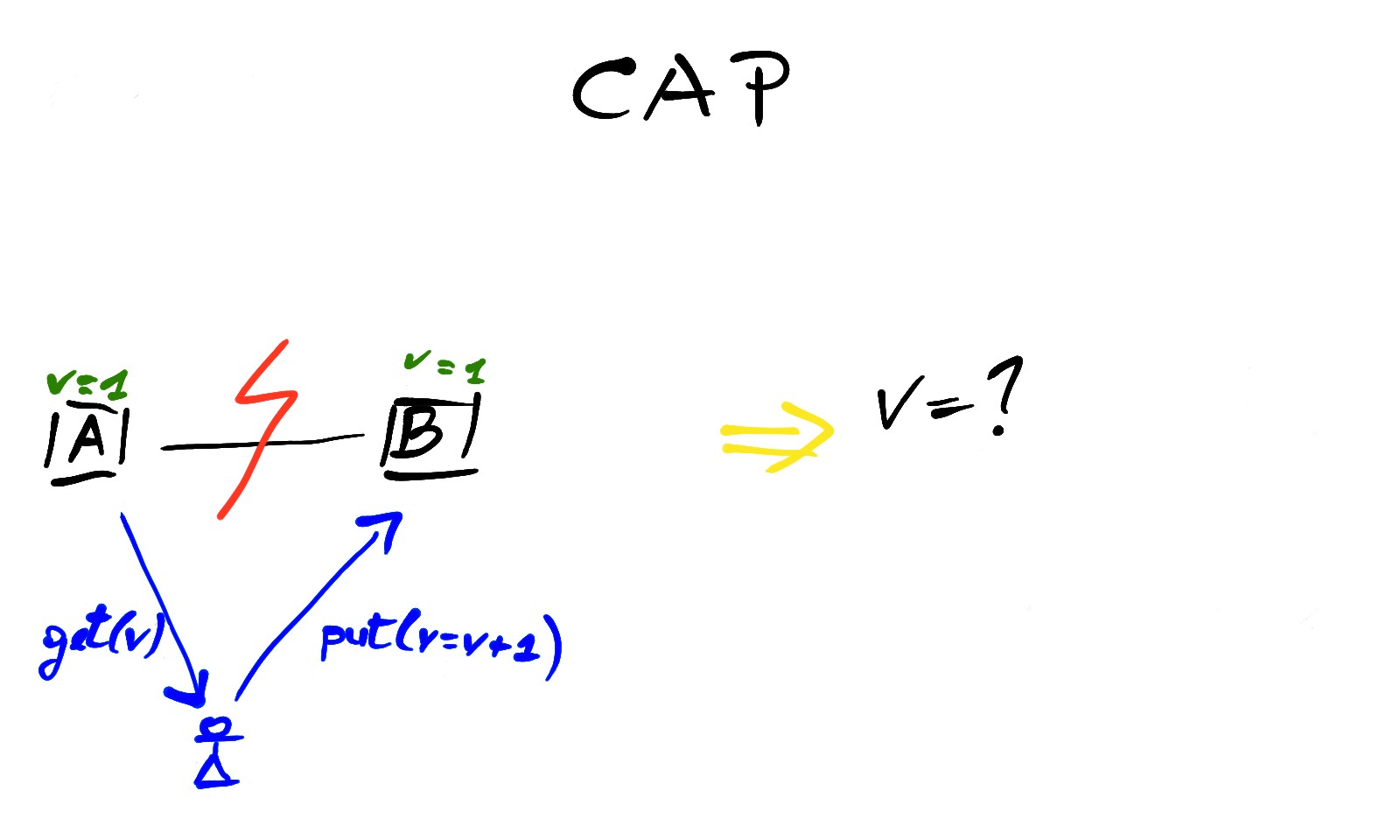

The CAP theorem is a very simplistic result in distributed systems, but although its practical utility is questionable it is still a good starting point to understand the tradeoff between availability and consistency. The theorem states that in a distributed system where partitions (communication failures between nodes or groups of nodes) may occur you can only choose one between Availability and (strong) Consistency. Or if you prefer: Consistency, Availability and Partition tolerance, pick 2 out of 3.

Roughly speaking, a service is Available when it provides meaningful responses to client requests. Strong Consistency is a more subtle concept but for now we can say that, from the client perspective, a consistent system behaves like a single node system. In other words, the client can assume that all the operations on the system happen as a linear sequence of actions, so if we read a data from two different nodes at the same time we should get the same value, just like there was a unique copy of that data in the system, that’s why Consistency is often called Linearizability.

In real world scenarios the Consistency requirement is usually relaxed to a more easy going version, that’s why the adjective strong is used to specify how much you wish to tolerate in terms of non-consistent states.

For example, in a simple distributed system of two database replicas, A and B, when the link between them dies, they can choose to guarantee availability continuing to accept read/write from clients and eventually reconciling their state later, or they can decide to guarantee Strong Consistency, denying client requests in order to keep their state aligned, until the network link comes back to life.

To guarantee strong Consistency, a synchronous replication strategy between nodes can be enforced and this usually means some sort of price to pay in terms of Availability, which is something that the paper authors didn’t want to happen, ever. Just to be sure that we are on the same page, the purpose of Dynamo is to accept requests from clients hence the system design has to maximize availability. To do so it’s necessary to gracefully tolerate temporary node disconnections, propagating the updates in the background asynchronously and reconciling the state of the nodes later.

The Dynamo approach is based on the idea of eventual Consistency, which means that in case of partitioning, the nodes will keep serving requests, resolving conflicts later. So conflicts are temporary and eventually nodes will come to an agreement but of course until they do, they will have to decide:

- when to perform the process of resolving update conflicts (e.g. during reads or writes? Dynamo chooses to always accept writes and to resolve conflicts during reads)

- who performs the process of conflict resolution (e.g. the data store or the application? the first choice allows simplistic reconciliations like Last Write Wins, while the application can usually make more sensible choices based on the user’s needs)

Other key principles followed (or we should say proposed) by Dynamo are:

- Scale incrementally one node at a time

- Every node must have the same responsibilities

- Decentralized peer-to-peer system

- The system needs to distribute work proportionally to the capability of the nodes (to favour heterogeneity of hardware setups)

System Interface

Dynamo’s interface exposes two operations:

get(key)locates the object replicas associated with thekeyin the storage system and returns a single objects (or a list of objects with conflicting versions) along with a contextput(key, context, object)determines where the replicas of the object should be placed based on itskeyand persist the replicas,contextencodes system metadata about the object (e.g. its version).

An hash of key is calculated to determine the storage nodes that will be responsible for storing/serving the key.

Partitioning

When we say that we want the system to scale incrementally, we’re basically requiring a mechanism to dynamically partition the data (key-values) over a set of nodes that may change and that we would like a smooth process to allow a new node to join the party. This is done via consistent hashing.

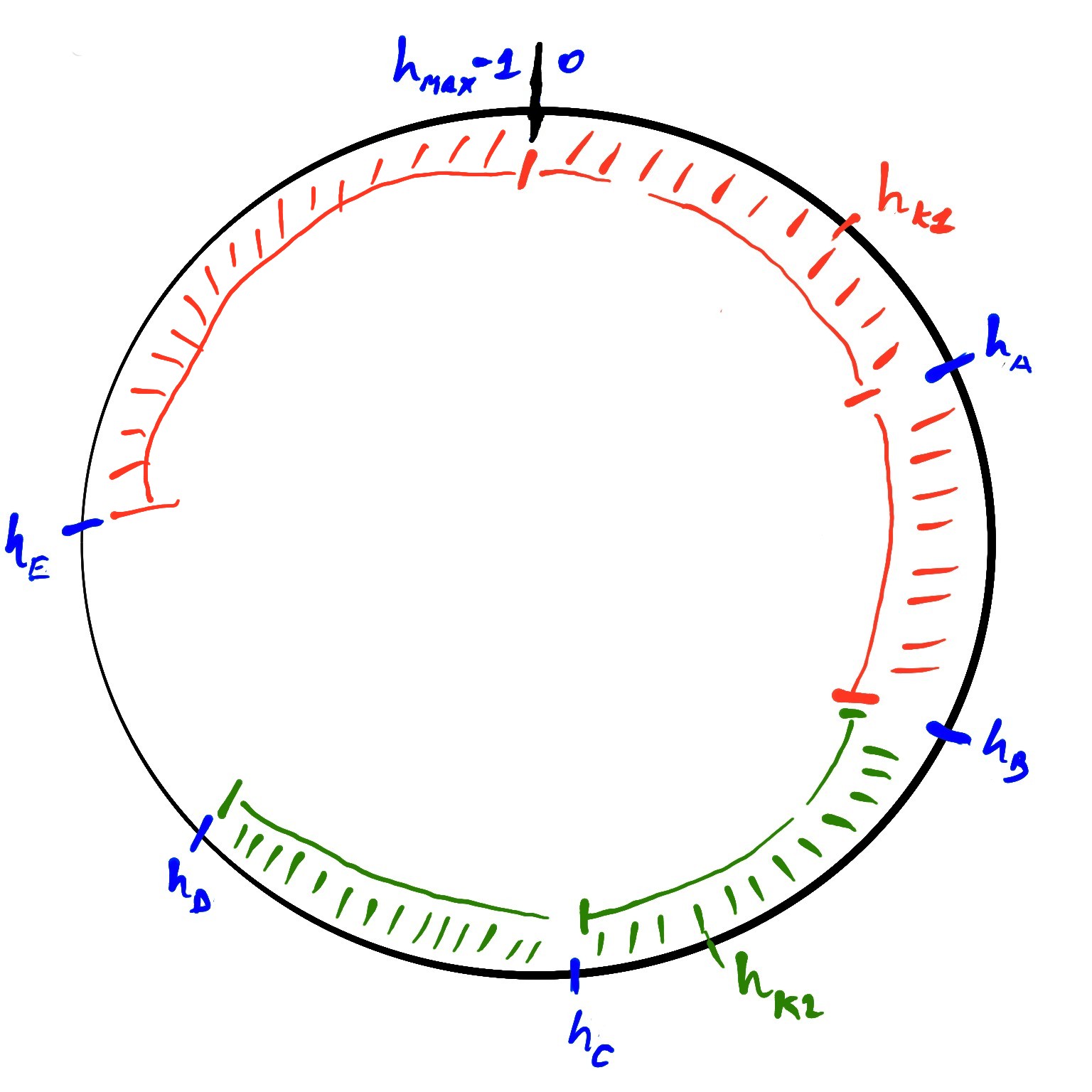

The output from the hash function used (MD5) is a 128-bit number and in consistent hashing it’s treated as a circular space, which means that the immediate follower of the max value that the hash can generate is the smallest one.

Each node in the system is associated with a random value by the hash function that will determine where the node will stand on the ring. The same is done for a key and once we’ve placed it according to its value we start walking the ring clockwise to find the first node which has a position larger than the key. This way, every node is responsible for the region of the ring between itself and its predecessor on the ring. Any departure or arrival of a node only affects its immediate neighbors while other nodes remain unaffected.

Replication

When you store your data in a system you don’t want it to disappear on the other hand you want it to be there for you when you need it, which means that the data must be both available and durable.

Replicating your data through multiple nodes is a common solution to mitigate the outcomes of node failures and to provide a more scalable solution to serve client requests. This often translates into better availability, even though going multi-node usually brings in concurrency issues, like the aforementioned consistency.

So each data is replicated and lives on different nodes (how many nodes is a parameter that can be configured). A key is assigned to a coordinator node which is in charge of the replication of the data items placed in his competence area on the ring of values given by the consistent hashing. A key is then copied by the coordinator node on a given number of nodes that are placed next to the coordinator on the hash ring (in clockwise order). Each node will hold the values for a given number of keys that he’s responsible for and for a given number of keys replicated from other responsible nodes.

The list of nodes in charge of storing each key is called the preference list, so that even if a node fails there are others to cover for specific keys.

Consistent hash

Let’s say we want to achieve partitioning and replication using consistent hash.

The hash function we will use, will return integer values in the range of [0,...,h_MAX-1]. The hash function determine the position of a node on the ring and consequentially the portion of ring that the node is in charge of. On the other hand the hash function is used to partition the keys among the nodes.

For a more concise notation we will say that h_k1 = hash(k1) is the hash value for key h_k1 and thus for every key and every node we will have h_k1, h_k2, h_B, etc…

Suppose we want to insert the two keys, k1 and k2 and that the nodes of the system are A, B, C, D, E.

Let’s start with k1. We first calculate its hash value h_k1 and we will use it as the starting position on the ring, then we start walking clockwise searching for the next node (or more precisely for its hash value) and finally we find h_A.

So A will be the node responsible for storing k1. We can now decide to replicate the key at other nodes to increase durability and availability. For the sake of this example one replica is enough, so the key k1 is asynchronously copied to the node that follows A on the ring, which is B.

Same thing happens if we want to store k2, the first node that we find on the ring is C and the following which will keep its replica, is node D.

Please note that, since the hash values are arranged in a ring structure, the node A is responsible for all the keys which have hash values smaller than 0 and greater than h_E.

Please note that any issue with one of the nodes will affect only its neighbours that will keep serving on behalf of the failed node.

To clarify further:

- Node

Ais responsible for the keys with hash value betweenh_Eandh_A - Node

Bis responsible for the keys with hash value betweenh_Aandh_B - Node

Cis responsible for the keys with hash value betweenh_Bandh_C - Node

Dis responsible for the keys with hash value betweenh_Candh_D - Node

Eis responsible for the keys with hash value betweenh_Dandh_E

Furthermore, in this particular example a replica for every key in a node is kept on the next following node on the ring, which is B for A, C for B and so on. To wrap everything up, B will contain all the keys with hash value between h_A and h_B and all the keys with hash value between h_E and h_A, this is true for every node.

This is a very simplistic model, because it doesn’t take into account, for example, that two adjacent nodes may be physically hosted on the same server which would not be great if we want to tolerate server faults. Furthermore different values for a key can occur, so we will need to find an agreement mechanism, like quorum for read/write operations and so on.

Versioning

As we mentioned in the example, one thing that could happen if you propagate changes on data asynchronously is that you will end up with inconsistent states, which means you could have a key that could have different versions of that same data at the same moment.

Each different version of the data may live its own life span until they are reconciled one way or another (by the client application or by the nodes in the system). The history deriving from each version may imply a causality chain between versions and subversions, to capture this dynamics, Dynamo uses vector clocks.

To be (a little bit) more specific, in Dynamo a client that wants to update an object, needs to specify which version is receiving the update, this information is provided by the client in the aforementioned context.

Vector clocks helps to tell the parallel relation versus the causal relations between two updates

For further readings about ordering of events in distributed systems, I would recommend Time, Clocks and the ordering of events in a Distributed System by Leslie Lamport. You can find a copy of this paper here.

Read/Write operations

Every node partecipating in Dynamo can receive an client request for any key.

The way a client chooses which particular node to query is up to the kind of routing strategy we want to use:

- the client may be somehow aware about, key partitioning, node topology and system load (using a Dynamo library);

- the client may rely on a systemn load balancer that will take care of forwarding the request to the appropriate node.

The list of nodes storing a data object is called its preference list. The primary node handling read/write operation is known as the coordinator, typically this is the node on top of the preference list. The first N nodes of the preference list will be involved in the r/w operation.

To keep replication consistent, Dynamo uses a quorum protocol. The protocol has two configurable paramenters R for reads and W for writes, they are the minimum number of nodes that must complete a successful read or write operation respectively. The term quorum is used because we can consider R and W to be the minimum number of votes (hence quorum) that we need to validate an operation. If R + W > N the latency of an operation is given by the slowest of the R or W nodes involved in the operation.

Wrapping up

Dynamo is a distributed data store that focus on Availability and provides eventual Consistency that was designed and developed to support business critical services at Amazon. The data objects stored have the form of a key:value pair and the requests on those objects were simple, non transactional and unstructured queries in the form of read/write (get/put).

We have explored the relationship between Availability and various levels of Consistency in case of network partitioning. Dynamo is based on peer nodes that can handle client requests and forward them to coordinator nodes.

Dynamo uses two techniques to achieve durability, availability and scalability:

- Partitioning, data objects are partitioned among nodes using consistent hashing, a technique that allows nodes to be added at any time while failing nodes will have only local effects;

- Replication, data objects are replicated on different nodes and a quorum-like system is used to confirm succesful operations.

In case a conflict between different version of data objects occur, a technique called vector clock is used.